Xi Jinping’s signature policy is about more than just infrastructure

BY: ALEK CHANCE

The Chinese Communist Party’s inclusion of the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) in its constitution on October 24 proves, beyond any reasonable doubt, that the concept has a central and significant place in China’s foreign policy. At the same time, those focused on the challenges that Chinese overseas infrastructure development currently faces view the initiative as a risky, and perhaps overblown venture. Some analysts have argued that China will be unable to maintain high rates of lending for long, and one American economist has pronounced the program an infrastructure investment “dud.” To square this circle, it is important to reconsider BRI as something more than just an infrastructure program. In fact, it is arguably a road map for China’s transition to a new level of economic development, one that also provides us with glimpses of its view for the future of globalization.

Looking back at the official “Visions and Actions” white paper, it is clear that BRI was always intended to be a comprehensive vision of Chinese policy from the outset, and not simply an infrastructure program. The document envisions a plan for linking China’s evolving economic development with that of its Eurasian neighbors; for enhancing connectivity; developing new standards for communications and energy technologies; increasing the ease of cross-border, multi-currency transactions and further internationalizing the use of the renminbi. As much of the world focuses on infrastructure, China seems to have been working diligently on all five “pillars” of BRI: policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration and cultural exchange. This is evident in the Belt and Road Forum outcomes, which may be lacking in depth, but not comprehensiveness. China has partnered with the European Union (EU) to work on new standards for 5G mobile communications, and has laid the groundwork for renminbi-denominated international financial transactions, creating networks in a space long dominated by American institutions and the U.S. dollar.

One of the least-discussed, but increasingly noticeable aspects of BRI is its focus on people-to-people ties and cultural significance. Official rhetoric surrounding BRI has, from the outset, tied together several related themes with the concept of the “Silk Road Spirit.” The “Visions and Actions” document opens with a description of how the sentiment arose along the ancient trading route:

“the Silk Road Spirit – ‘peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit’ […] Symbolizing communication and cooperation between the East and the West, the Silk Road Spirit is a historic and cultural heritage shared by all countries around the world.”

The opening of President Xi Jinping’s keynote speech at the May 2017 BRI Forum touched upon these points, nearly verbatim. Government websites and state media continuously portray BRI as a positive, intercultural exchange, and hearken back to an age in which great civilizations and religions shared their wisdom via the Silk Road. In 2014 (one year after the announcement of BRI), China successfully made a joint submission, along with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, to have the Silk Road placed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. China also hosts a Silk Road International Film Festival, which is committed to promoting “mutual understanding” and numerous art exhibitions with titles like “Silk Road: Reflection of Mutual Learning.” Chinese media outlets and cultural institutions appear to be cultivating a narrative of globalization in which China played a central and ostensibly benign role. In this old “Silk Road Spirit,” which Xi Jinping seeks to make anew, value-indifferent trade—not politics—drove interconnectedness and the advance of civilization.

Official rhetoric also reliably frames the context of BRI within supposedly observable trends towards a “multipolar,” “globalized” and “culturally diversified” world. These phrases are often used to articulate foundational principles of Chinese foreign policy, more generally. Moreover, they constitute implicit critiques of a perceived hegemonic or unipolar American-led order in which diversity (of regime-types at least) is not respected, and in which mutual benefit, win-win cooperation and other principles of sovereign equality are not genuinely embraced. In other words, rhetoric surrounding BRI reliably hits all the notes of the so-called Chinese “pluralist” rather than “liberal” vision for the future of the international order. This differentiation is evident in other talking points regarding BRI: it is not the Marshall Plan, nor is it even to be referred to as a strategy.

If BRI’s inward-facing reality is that it is a comprehensive plan for advancing China’s economy to the next level, its outward-facing reality is that of a comprehensive rebranding of China as the focal point in the next stage of globalization. This pluralistic, “open,” and multicultural global order will not have a “leader” like the current iteration, but it will certainly have a center of gravity.

At the diplomatic and strategic levels, publicly endorsing BRI carries implications for the future character of trade, financial connectivity, infrastructure-led development and global governance. The overall approach and the rhetoric consistently seeks to promote a Chinese vision of multipolar global governance, an important element of which is the rejection of prioritizing democratic norms or providing external foundations from which to challenge state sovereignty. As an aspect of China’s continuing inability to allow for a more market-driven economy, BRI also represents and enables a potential shift in leading economic norms. It is of course perfectly natural and expected that China’s signature foreign policy initiative will reflect its broader normative vision for world politics. But, prospective partners or BRI supporters must carefully evaluate the degree to which the initiative may impact other areas, such as environmental and social safeguards and Internet governance. Such an evaluation must draw on existing studies of BRI’s centrality to China’s long-term economic planning, and an awareness—which should prompt further study—of how the initiative instantiates China’s vision for the future of globalization.

Alek Chance, Ph.D., is a fellow at The Albert Del Rosario Institute in Manila and an international affairs consultant. His research focus is on U.S.-China relations, international order and the role of ideas in international politics. This article is adapted from the longer study “Checking in on the Belt and Road Initiative.”

The views expressed in this post reflect those of the author and not that of the EastWest Institute.

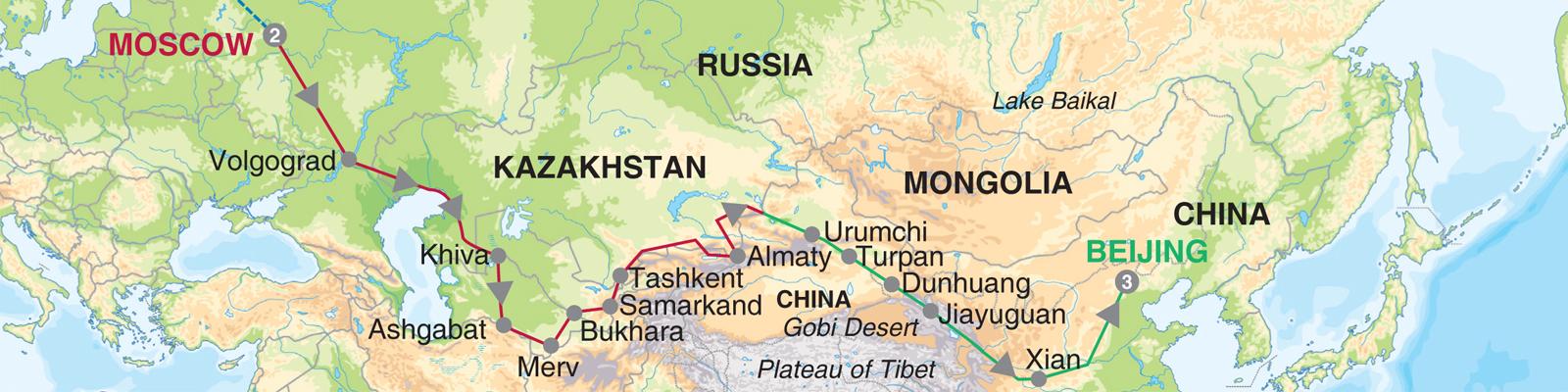

Photo: "Map of the Silk Road luxury train tour" (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Train Chartering & Private Rail Cars