The China-Pakistan Relationship

Writing for The News International, EWI Board Member Ikram Sehgal argues that Pakistan and China have good reasons to maintain their strong bilateral ties, and that Pakistanis should not be alarmed by China’s recent overtures to India.

Visiting China is a never-ending revelation; the amazing 7.7 percent growth rate in a sluggish global economy is considered ‘disappointing’ there. Of China’s 31 provinces, Guangdong has the highest GDP – US$960 billion with a growth rate of 8.2 percent – while Tibet is lowest with 12 percent growth rate and a GDP of US$11 billion.

The Guizhou province has the highest growth rate (12 percent). Xinjiang, bordering Pakistan and vastly underdeveloped, is 25th with US$121 billion and a 12 percent growth rate. The expanse of the two bustling ever-growing mega cities of Beijing or Shanghai is truly outstanding with enormous public infrastructure delivering efficient services to its citizens.

An early morning (7:15am) extempore briefing by CH Tung at the EastWest Institute’s 2013 ‘spring’ board meeting in Beijing from May 15 to May 17 was a treat. The shipping magnate became Hong Kong’s chief executive in 1999 when the city was handed back to China by the UK. Born on July 8, 1937 – the day Japan and China went to war – Tung gave an insightful historical and cultural perspective into China describing the determined mindset influencing China’s drive to soon become the most prosperous country in the world.

Certainly important to peace and prosperity in the world, the US-China competition is presently peaceful but has ominous military overtones because of the growing number of flashpoints on China’s periphery. The US is mired in Cold War relationships that it cannot seem to shed. Of greater concern to us are Pakistan’s present and future ties with China.

China’s only opening to the world was symbolised best by Pakistan facilitating its first top-level contact with the US – Henry Kissinger’s famous secret trip to China in July 1971 changed the strategic dynamics of the world. Chinese PM Chou En-Lai reportedly told Kissinger, “Do not forget the bridge (meaning Pakistan) you have used, you may have to use it again.” Unfortunately our record with the US is spotty, every ten years or so Pakistan goes from being a ‘cornerstone’ to a ‘gravestone’.

The Chinese leaders from the 1970s are retired octogenarians now. However, China has not forgotten the ‘bridge’ that Pakistan is, at least at the strategic level. The proposed Pak-China economic corridor linking Gwadar Port with Xinjiang and other parts of China will involve both road and rail links, with both optic fibre and oil pipelines for boosting energy, trade and transport between the two countries. Initially investing over US$20 billion creating a ‘Special Economic Zone’ in Xinjiang, China’s keenness to have another trade outlet to the Indian Ocean is cementing its historic ties with Pakistan.

The transit time will be reduced from weeks and months to three to four days only, creating an economic windfall for Pakistan, particularly in less developed Balochistan. Pakistan’s salvation requires major investment in infrastructure. With the US pulling out of Afghanistan by 2014, the Afghan economy will go into a tailspin. Only an economic overdrive can contain the spill over of the desperate poverty. Militarily we will be hard-pressed, force-multiplied further if we fail to create economic opportunities for our people as well as the Afghans.

The high point of my current visit to China was meeting up with retired ambassador Zhang Chun Xiang. Four decades ago he was an interpreter with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) divisions constructing the tremendous Karakoram Highway (KKH) in the highest mountains in the world. Pakistan Army Aviation’s KKH Flight was in support with two Aloutte-3 helicopters.

Ambassador Zhang speaks fluent Urdu and is not averse to choice Punjabi expletives if and when the need arises. He served as the Chinese consul general in Houston, retiring as China’s ambassador to Hungary. His 23 years of service in Pakistan includes stints with the Chinese consulate general in Karachi and the Chinese embassy in Islamabad. His last posting in Pakistan was as ambassador. Now in an advisory capacity with major Chinese technological group Huawei, Zhang still advises on Chinese policies in South Asia.

The EastWest Institute honoured Ambassador Zhang by his brief presence at the EWI Board meeting. People like Zhang have kept the friendship alive not only between individuals but countries, our mutual association being highly symbolic of the continuing friendship between China and Pakistan. Emotions and feelings will always drive relationships between nations. And, more importantly, core interests must coincide – and better still, not diverge.

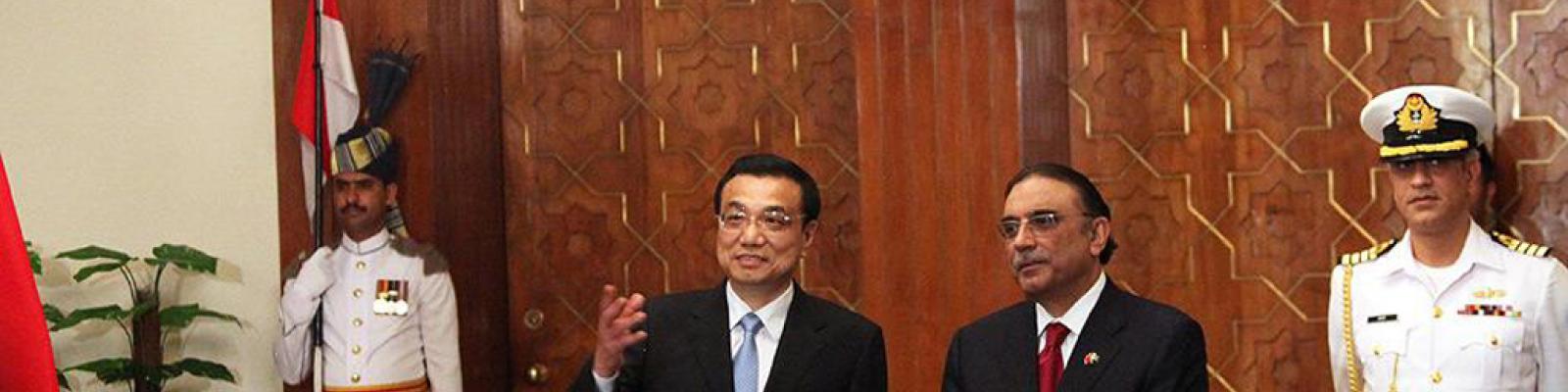

The disappointment in Pakistan that Chinese PM Li Keqiang chose India as his first stop as prime minister (with Islamabad to follow later) is more perception than fact. We should not be apprehensive of China-India relations; they will have no negative consequences for Pakistan. Similarly we cannot condition our ties with the US on its ties with India – the dynamics are different particularly given the economic connotations. Our ties with China will become stronger as mutual economic initiatives increasingly dovetail into their geo-political compulsions. Take India’s questioning of the Chinese policy of issuing stapled visas to residents of Indian-occupied Kashmir in contrast to giving normal visas to citizens of the Pakistan-administered side. India says China is taking Pakistan’s side in the dispute. That is true!

India’s trade with China exceeds US$66 billion but unresolved border disputes remain. Historically China is a restraining factor to India’s normal aggressive posture vis-à-vis Pakistan. India’s apprehensions about Gwadar are neither justified nor warranted. The Chinese PM will possibly underscore the port’s importance to China, not as a forward military base but an energy and trade junction providing a vital economic outlet for the country. Regional peace and stability requires we address contentious issues that bedevil relations, like Kashmir, between India and Pakistan. Given that we can never come to an agreement over Kashmir, what is stopping us from coming to an arrangement?

To quote Director Sun Shi-Lai of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences “Pakistan can cast great influence on Islamic countries and serve as a bridge between China and the Middle East.” Fortunately China’s self-interest and our national interest coincide, reinforcing mutual commitment as “all-weather” friends (to quote Chinese FM Wang Yi). Our friendship is definitely a ‘cornerstone’ of Chinese foreign policy. With over US$20 billion being invested in Xinjiang this year alone, China’s opening to the Indian Ocean is not only a dream of prosperity for China and Pakistan but a dire necessity.

The Chinese suffered many casualties during the construction of the KKH. As helicopter pilots it was our unpleasant duty to ferry the injured for medical aid – some of them with fatal injuries. For me personally at that time it was a road coming from nowhere and going nowhere. The proximity to blood and gore on a daily basis does get to you. After one particularly harrowing day I angrily asked Zhang, “What is with you Chinese? Why are you killing yourselves for this road?” His calm reply is forever etched in my memory, “You Pakistanis cannot think beyond 10 years, us Chinese dream beyond a 100 years!”

What stops us Pakistanis from dreaming too?

Ikram Sehgal is a security analyst and chairman of PATHFINDER GROUP.