CPEC: Pakistan’s Road to Glory?

China and Pakistan have been faithful allies since the early 1950s. The Sino-Pak relationship has proved to be fundamental for both countries, deriving mutual benefits from their strong diplomatic alliance and economic ties. Therefore, it came as no surprise when Pakistan welcomed President Xi Jinping in April 2015 to inaugurate the “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor“ (CPEC), a key project under China’s ambitious One Belt and One Road Initiative (OBOR).

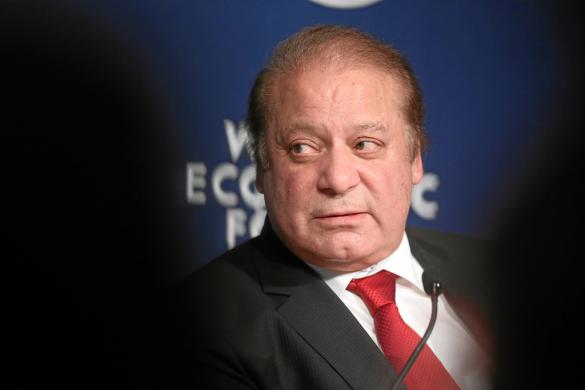

CPEC is designed to connect the city of Kashgar, in China’s landlocked Xinjiang province, to the port city of Gwadar in Pakistan’s Baluchistan province, offering a vital infrastructural network linking China to the Arabian Sea. CPEC commits Pakistan’s land and resources to a massive 62 billion USD investment that will have tremendous socio-economic and geopolitical implications for the partnering nations and the region as a whole. Pakistan’s then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who advocated for the venture, characterized CPEC as a “game changer” that would bring about a transformational change and pull the nation out of its economic misery.

Indeed, Pakistan’s financial and geostrategic position may enjoy a considerable advantage courtesy of CPEC. However, any real gains will require an appropriate execution of this ambitious initiative coupled with a sound understanding of how the Sino-Pak collaboration will relate to the competitive interests of major regional stakeholders, in particular, the U.S. and India.

Perceived Gains

The planned 15-year-long collaboration encapsulates projects that span across Pakistan’s five provinces, focused on improving the country’s infrastructure and power generation capabilities while producing an estimated 700,000 jobs. Unfolding at a steady pace, approximately 19 projects have reached completion making it the fastest developing of OBOR’s proposed corridors.

China’s investment has fostered greater economic activity in Pakistan and paved the way for a more robust GDP growth. Pakistan now ranks 115th on the World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness scale for 2017-18, a jump of seven positions over the previous year, and earlier this year was upgraded to the MSCI Emerging Market Index, which has further enhanced prospects for future foreign direct investment. Additionally, the World Bank, in its Pakistan Development Update for 2017, projected that the nation’s economic growth could reach 5.8 percent in 2019, partially owing to the investment inflows from CPEC. Moreover, CPEC has managed to attract interest from Iran, as conveyed by President Hassan Rouhani last year, as well as from Russian investors who are keen on exploring investment options.

Importantly, Pakistan’s global image has also undergone a drastic makeover. Where Pakistan was harboring fears of isolation and was largely being overlooked for its extremely volatile security situation, it is now increasingly being recognized as an important regional player in South Asia.

Economic and Geopolitical Realities

While CPEC paints a promising picture, not everyone is optimistic about this venture. Business insiders have expressed grave concerns that China will have a disproportionate economic advantage, a sentiment validated by a breakdown of CPEC’s recently published “Master Plan.” For instance, the plan briefly highlighted how Chinese investments are tailored to facilitate the Kashgar Prefecture, and also mentions China’s aspirations towards building the largest textile production and export processing base in Xinjiang. Such developments would mean a serious competitive disadvantage for Pakistan’s textile sector and local industries in general.

Furthermore, Pakistan’s provinces have always been divided by their own self-interests and it is only a matter of time before these divisions pose barriers to CPEC’s progress. Today, the tribal leadership in Balochistan views CPEC as a tool for exploitation that compromises local rights and interests and has warned both the government and China to halt the project with immediate effect. Equally critical are the emerging security concerns such as the recent grenade attack on Gwadar Port, while the murder of two abducted Chinese nationals has created a daunting scenario for the safety of the deployed workforce necessitating Pakistan to establish a Special Security Division to guard CPEC.

Another major point of concern is asset risk. CPEC’s financing is primarily based on a set of Chinese grants and concessionary loans, and failure to deliver on financial gains means Pakistan will have much to lose, particularly considering the country’s track record of debt obligations to the IMF and World Bank. Under the pressure of such exorbitant loans, Pakistan could be in jeopardy of forfeiting a stake in its own land and resources. This prospect has prompted certain Pakistani lawmakers to compare CPEC with the East India Company, arguing that any incoming capital could very well be offset by an even greater outflow. The handover of the Hambantota Port following Sri Lanka’s debt crisis and inability to repay 301 million USD to China is often raised as an example of what could go wrong in Pakistan.

Within this context, the increasingly close relationship between the United States and India has also become a point of interest for Pakistan. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson recently suggested solidifying a free and open “Indo-Pacific” and endorsed India as a responsible regional partner. India has always maintained its stance against CPEC suggesting that the corridor passes through disputed territory and that it is non-compliant with the Indian ideals on “Belt and Road” projects. On the other hand, the U.S. has a strong interest in sustaining a balance of power in Asia and maintaining regional stability. However, the Trump administration has expressed doubts over Pakistan’s role as a counter-terrorism ally, straining current relations. Arguably, U.S. support of India’s claims could further add fuel to the fire and create bottlenecks for CPEC.

The Road Forward

Driven by geostrategic interests, China’s architecting CPEC means it is naturally the frontrunner for the lion’s share of anticipated returns. In contrast, Pakistan’s bifurcated leadership, administrative inadequacy and lack of operational transparency make it imperative for the incumbent government to prioritize effective project implementation and to exercise sustainable long term policies if it wishes to achieve envisioned gains. The highly anticipated CPEC Long Term Plan is set to be finalized at the upcoming 7th Joint Cooperation Committee meeting in Islamabad and should provide a more realistic benchmark for Pakistan’s cost and benefit analysis.

Pakistan’s policymakers also have a crucial task at hand in balancing the possibly broad implications of the growing U.S.-India nexus. Pakistan cannot afford to lose its alliance with the United States if it wishes to safeguard its national security in the long run, necessitating enhanced bilateral cooperation that recognizes areas of shared interests and encourages the U.S. to adopt, at a minimum, a neutral perspective on CPEC, appreciating its potential value for Pakistan.

CPEC remains a remarkable initiative and many of its industrial and economic benefits are already materializing. Ultimately, despite internal and external pressures, Pakistan’s ability to adequately leverage and monetize this commitment will determine CPEC’s real worth to its economy, its citizens and its standing in the region.

Farwa Aamer is a Research Associate for the EastWest Institute’s Asia-Pacific Program.

The views expressed in this post reflect those of the author and not that of the EastWest Institute.

Photo credit: "Xinjing 2013 mountains Pakistan border_M" (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by peteropaliu